For millions of family caregivers, the fear of a loved one wandering is a constant, quiet anxiety. The statistics underscore this concern; according to the Alzheimer’s Association, six in ten people with dementia will wander at least once, with many doing so repeatedly. This isn’t just a matter of getting lost; wandering can lead to serious injury, exposure to harsh weather, or worse.

Imagine the story of Maria and her father, Luis. One evening, she found him at the front door, keys in hand, insisting he needed to get to a job he hadn’t had in twenty years. This moment, filled with confusion and fear, is a reality for countless families. It’s a sign that the home, once a sanctuary, now requires a new layer of safety and understanding.

This guide was created to turn that anxiety into action by providing practical, evidence-based wandering prevention strategies to help you create a safer environment. Our goal is to empower you with knowledge and comprehensive guidance to help your loved one continue living safely at home. You are not alone, and there are concrete steps you can take today.

Understanding Wandering: Definition and Scope

In dementia care, “wandering” is more than just aimless walking. It refers to a person with cognitive impairment moving about in a way that may be disoriented, unsafe, or seem to lack purpose. For a caregiver, it might look like restless pacing, repeated attempts to leave the house, or becoming lost in a familiar neighborhood. It’s crucial to understand that this behavior is a symptom of the disease, not a willful act of disobedience.

The person is often trying to fulfill a need, respond to a memory, or escape a source of stress they can no longer articulate. While most commonly associated with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, wandering-like behaviors can also occur in individuals with other conditions.

| Condition | Common Wandering Characteristics |

| Dementia/Alzheimer’s | Often goal-oriented from their perspective (e.g., “going to work”), it is triggered by memory loss or confusion. |

| Parkinson’s Disease | It can be linked to medication side effects, confusion, or psychosis. |

| Autism Spectrum Disorder | Often related to elopement or “bolting” from overstimulating environments or towards an object of interest. |

| Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) | It may stem from restlessness, confusion, or frontal lobe damage affecting judgment. |

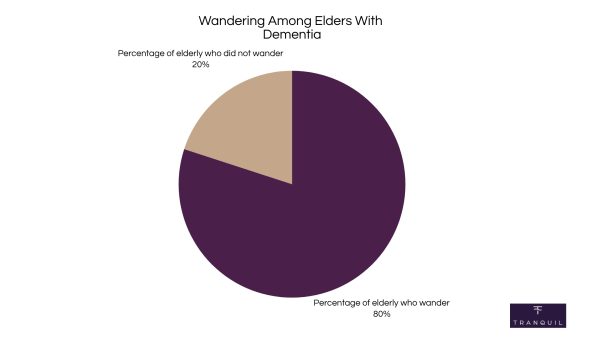

Wandering risk isn’t static; it changes with the progression of dementia. 4 out of 5 (80%) elders with dementia will wander multiple times. While it can happen at any stage, it typically peaks during the middle stages. This is when a person is still physically mobile but their cognitive decline has become significant, leading to disorientation and impaired judgment.

Key Insight: Wandering risk peaks in the middle stages of dementia. This is a dangerous period where individuals often retain physical mobility but suffer from severe cognitive decline and impaired judgment.

Why Does Wandering Happen? The Underlying

Causes and Risk Factors

Understanding the “why” behind wandering is the first step toward effective prevention. The behavior is rarely random; it’s almost always a response to an internal or external trigger. By identifying these triggers, you can proactively address the root cause of the behavior.

A. Cognitive Factors

The brain changes associated with dementia are a primary driver. A person may not recognize their own home, believing they are in the wrong place. Time-shifted memories can make them think they need to pick up children from school or go to a long-forgotten job, compelling them to leave to resolve the confusion.

B. Behavioral and Psychological Factors

Emotional states play a huge role, as agitation, anxiety, or boredom can lead to a desire to escape. Sundowning, which is increased confusion in the late afternoon, is a common trigger. Some wandering is also “purpose-driven,” where the person is trying to fulfill a past routine but may continue walking for miles without realizing it.

C. Medical Factors

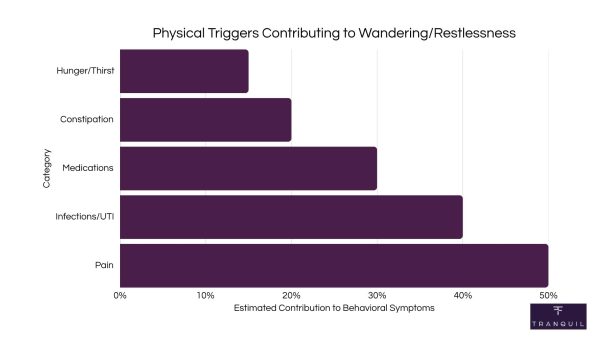

Underlying physical issues can cause discomfort that the person cannot communicate. Research indicates that physical triggers account for a significant portion of wandering and restlessness in dementia:

- Untreated pain (30-50% of cases) is the leading physical contributor to agitation

- Urinary tract infections (20-40%) are linked to acute delirium in elderly patients, often manifesting as restlessness or increased mobility

- Medication side effects (15-30%) can cause dizziness, confusion, or agitation

- Constipation (10-20%) creates discomfort that may drive pacing and restlessness

- Hunger or thirst (10-15%) can trigger searching and wandering behaviors

These percentages often overlap, as individuals may experience multiple unmet needs simultaneously. For instance, a person taking anticholinergic medications may also be experiencing untreated pain and constipation, creating a compounding effect that significantly increases wandering risk.

D. Environmental Factors

The immediate environment can be a powerful trigger. Excessive noise, clutter, or poor lighting can be overstimulating and stressful. Conversely, an under-stimulating environment can lead to boredom. Calming design tips include using soft lighting, reducing clutter, and labeling key rooms to reduce confusion.

Pro Tip: When restlessness occurs, first check for physical needs. Uncommunicated pain, hunger, thirst, or the need to use the restroom are common and often overlooked wandering triggers.

Warning Indicators and the Dangers of Wandering

Early Warning Signs a Person May Wander

Proactive wandering prevention starts with recognizing the subtle cues that may precede an event. If you notice a new or increasing pattern of these behaviors, it’s a sign to reassess and enhance your safety measures:

- Constant pacing, especially near doors or windows.

- Verbally expressing a desire to “go home,” even when they are home.

- Attempting to fulfill past obligations, like “going to work” or “driving the car.”

- Seeming lost or disoriented in a familiar environment.

- Rummaging through drawers as if looking for something they need to leave.

- Experiencing reversed sleep cycles, being more active at night.

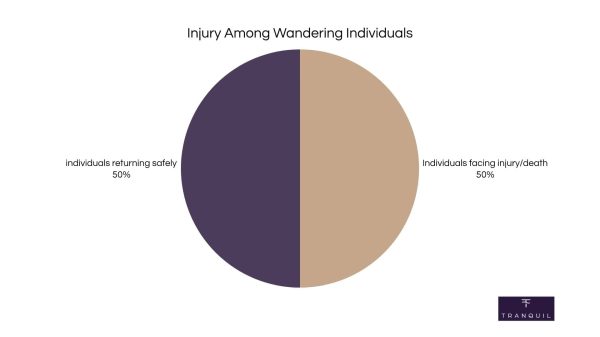

Statistics and Public-Safety Impact

The consequences of wandering can be severe. If a person is not found within 24 hours, up to 50% of wandering individuals with dementia will suffer serious injury or death. The dangers are numerous and immediate: injuries from falls, dehydration or hypothermia, drowning, or traffic accidents.

Research has shown that a significant percentage of adults with dementia who go missing are found far from their homes, and the risk of a negative outcome rises sharply with each passing hour.

Important: The danger of wandering is extreme. If a person with dementia is not found within 24 hours, up to half will suffer serious injury or death.

A Multi-Layered Approach to Wandering Prevention Strategies

Effective wandering prevention isn’t about a single lock or device; it’s about creating layers of safety that address different triggers and scenarios. A comprehensive plan combines environmental safety, behavioral interventions, modern technology, and community support.

A. Environmental Modifications

The goal is to make the home a safe, calming space while reducing opportunities for unsafe exits. This involves securing the perimeter and making indoor navigation easier.

| Secure Exits: Install deadbolts high or low on the door, outside the person’s line of sight, and check local fire codes. Simple battery-operated door and window alarms can provide an immediate alert. | |

| Reduce Exit Cues: Place a dark-colored mat in front of doors, as some individuals may perceive it as a hole and avoid it. You can also use curtains or “stop” signs on doors to camouflage them. | |

| Enhance Visual Cues Indoors: Use signs with pictures and words to label important rooms like the bathroom. Night-lights in hallways and bathrooms improve safety. |

B. Behavioral and Routine-Based Strategies

Addressing the internal triggers for wandering is just as important as securing the physical environment. A structured, calming routine can significantly reduce anxiety and restlessness.

| Maintain a Consistent Daily Schedule: Regular times for waking, meals, and activities can provide a sense of security. | |

| Encourage Gentle Exercise and Hydration: A short walk during the day can help manage restlessness and ensure they are drinking enough fluids. | |

| Provide Meaningful Activities: Engage the person in simple, familiar tasks like folding laundry or sorting silverware. | |

| Use Calm Communication: If the person insists on leaving, avoid arguing. Instead, redirect gently with short, simple sentences and a reassuring tone. |

C. Technology and Identification Aids

Technology offers a powerful safety net when other strategies fail. A GPS tracker for elderly individuals can provide real-time location tracking, while other devices can alert you if a person leaves a specific area. These tools range from simple identification bracelets to advanced tracking watches.

When choosing a tracking device, consider factors like willingness to wear it, privacy settings, tamper-protection, and the burden of recharging. For many, a device that integrates seamlessly into their daily life is the most effective solution.

D. Community Programs and Services

Your local community can be a vital part of your safety net. Familiarize yourself with these resources before you need them.

- Project Lifesaver: This program provides a personal transmitter that emits a tracking signal for local law enforcement to use in a search.

- Silver Alert: A public notification system that broadcasts information about missing seniors with cognitive impairment.

- MedicAlert® + Alzheimer’s Association Safe Return®: A 24/7 nationwide emergency response service for wandering and medical emergencies.

- Local Police Registries: Many police departments maintain a free, confidential registry of vulnerable adults to speed up a search.

Pro Tip: For a simple first step, install battery-operated alarms on key doors and windows. They provide a cost-effective, immediate alert if a secure exit is opened.

Handling Special Situations

Wandering prevention needs to adapt when you leave the familiar environment of home. Planning is essential for travel, appointments, and using respite services. For air travel, call TSA Cares ahead of time for assistance. In a hotel, use a portable door alarm for extra security, and keep your routine as consistent as possible.

- Adult Day Centers: When visiting a potential center, ask specifically about their wandering prevention policies, staff-to-client ratios, and door security.

- Respite Care Facilities: Before a short-term stay, tour the facility. Ask the same questions you would for a day center, and ensure they have a robust plan to keep residents safe.

Planning Ahead: Your Emergency Response Plan

Even with the best prevention, a wandering event can still happen. A calm, swift, and organized response is critical. Do not wait; most experts agree that you should call 911 within 15 minutes of realizing your loved one is gone.

| Create a Personal Profile Sheet: Prepare a one-page document with a recent photo, height, weight, medical conditions, and habits to give to law enforcement. | |

| Establish a Neighborhood Alert Network: Inform trusted neighbors about your situation. Provide them with your contact information and a photo. | |

| Coordinate with Law Enforcement: Give the dispatcher your Personal Profile Sheet information. Let them know if the person has a tracking device, like a senior tracking watch, and provide login access if possible. | |

| Conduct a Post-Incident Debrief: After your loved one is found safely, review what happened. Were there new triggers? Are there gaps in your home safety? Acknowledge the stress of the event and seek support. |

Important: Do not wait to seek help. If you realize your loved one is missing, call 911 immediately. Most experts recommend calling within 15 minutes.

Essential Resources and Support for Caregivers

You cannot and should not do this alone. Caring for someone with a tendency to wander is physically and emotionally draining. Building a strong support system is a non-negotiable part of your wandering prevention plan.

- 24/7 Helplines and Support Groups: The Alzheimer’s Association offers a free 24/7 helpline at 800-272-3900 for immediate advice and local support.

- Prioritize Mental Health: The stress of constant vigilance is immense. Find short, effective ways to manage anxiety, and look into local respite care grants for a much-needed break.

- Address Legal and Financial Matters: It’s important to have conversations about legal issues like driving cessation and establishing a Power of Attorney before a crisis hits.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How common is wandering in Alzheimer’s disease?

It’s very common. The Alzheimer’s Association reports that 60% of individuals with dementia will wander at least once. For many, it becomes a persistent, recurring behavior.

Can medication stop wandering?

There is no specific medication to stop wandering. While some medications might treat underlying anxiety that triggers wandering, they often have side effects. The primary approach should be behavioral and environmental strategies.

What should I tell my neighbors?

Be direct and concise. Explain that your loved one has a memory condition and may get confused. Give them a photo and your phone number, and ask them to call you immediately if they see the person alone.

Is GPS tracking safe and private?

Reputable GPS devices use secure, encrypted technology. You control who has access to the location data, typically through a password-protected app. It is a tool for safety, not surveillance.

Key Takeaways and Your Next Steps

Wandering is a complex and challenging symptom of cognitive decline, but with a proactive, multi-layered approach, you can significantly increase your loved one’s safety. This guide is a starting point for creating a personalized wandering prevention plan.

- Assess and Modify the Environment: Secure exits and create a safe, easy-to-navigate home.

- Establish a Calming Routine: Use consistent schedules and meaningful activities to reduce anxiety.

- Consider Technology: Explore GPS aids, such as a dedicated dementia watch,

As a critical safety net. - Create an Emergency Plan: Know exactly what to do and who to call if your loved one goes missing.

We encourage you to use this guide to create a safer world for your loved one. By taking these steps, from environmental changes to using a GPS-enabled tracking watch for seniors, you are empowering them to continue living with dignity and independence at home.

References

Alzheimer’s Association. (n.d.). 24/7 Helpline: 1.800.272.3900. Alzheimer’s Association. Retrieved November 3, 2025, from https://www.alz.org/help-support/resources/helpline

Alzheimer’s Association. (n.d.). Wandering. Alzheimer’s Association. Retrieved November 3, 2025, from https://www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/safety/wandering

Alzheimer’s Association. (2023, August 9). Alzheimer’s Association 2025 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Association. Retrieved November 3, 2025, from https://www.alz.org/getmedia/ef8f48f9-ad36-48ea-87f9-b74034635c1e/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf

Mangini, L., & Wick, J. Y. (2017, June 1). Wandering: Unearthing New Tracking Devices. National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28595682/

Mayo Clinic. (2024, March 26). Late-day confusion in people with dementia. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved November 3, 2025, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/alzheimers-disease/expert-answers/sundowning/faq-20058511

Medicalert + Safe Return. (n.d.). MedicAlert® + Alzheimer’s Association Safe Return® is a nationwide program run in partnership between MedicAlert Foundation (“MedicAlert®“) and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association, Inc. (“Alzheimer’s Association”). Medicalert + Safe Return. https://alzbr.org/medicalert-safe-return/

Orgeta, V. (2025, October 11). Lived experiences of missing with dementia and pathways to care: a qualitative study of carers’ and professionals’ perspectives. Retrieved November 3, 2025, from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12512132/

Pozo, B. D., & Compton, M. T. (2022, January 11). Voluntary Registries: Filling the Critical Information Gap in First Response to Mental Health Crises. National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10782591/

Project Life Saver. (n.d.). Project Lifesaver International | Bringing Loved Ones Home. Retrieved November 3, 2025, from https://projectlifesaver.org/

Silver Alert: Alert Criteria. (n.d.). Indiana State Government. Retrieved November 3, 2025, from https://www.in.gov/silveralert/alert-criteria/

Wandering. (n.d.). Alzheimer’s Association. Retrieved November 3, 2025, from https://www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/stages-behaviors/wandering